30 BILLION EARTHS?

30 Billion Earths?

New Estimate of Exoplanets in Our Galaxy

By Robert Roy Britt

Senior Science Writer

posted: 07:00 am ET

29 January 2002

Chances are you haven't spent a whole lot of time wondering how many Jupiter-like planets exist in our galaxy. But Charley Lineweaver has, because it bears on a more important question: How many potentially habitable planets are there?

New calculations by Lineweaver and Daniel Grether, both of the University of New South Wales in Australia, provide an encouraging answer to this question. The researchers expect a flood of Jupiters will be found, perhaps 50 percent more than currently expected.

Each such discovery would be significant in the hunt for planets that could harbor life.

Each such discovery would be significant in the hunt for planets that could harbor life.Why? Because much of the evolution of our own solar system, including the formation of Earth, was orchestrated or affected by Jupiter, the largest planet with by far the bulk of the solar system's mass, excepting the Sun, of course.

"Our solar system is Jupiter and a bunch of junk," as Lineweaver puts it.

Our protector

When Jupiter developed, it simply bullied other objects into position or out of existence. Then the mighty gas giant became Earth's protector.

Though the fledgling Earth was pummeled by asteroids and comets, making it difficult for life to take hold, it could have been much worse. Jupiter shielded Earth from an even heavier bombardment of debris that made its way from the outskirts of the new system toward its central star.

That protective role continues. In 1994, Jupiter used its immense gravity to lure comet Shoemaker-Levy into a death plunge. Had the comet hit Earth, it would have sterilized much or all of the planet.

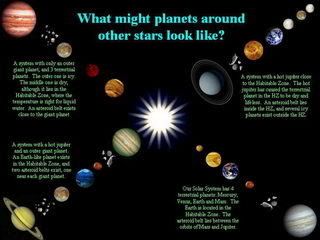

For now, no one knows whether our solar system represents a common method of formation and evolution. In fact, discoveries over the past six years seem to indicate otherwise. Most of the roughly 80 planets discovered outside our solar system are much more massive than Jupiter. They also orbit perilously close to their host stars, locations that would likely prevent rocky planets from forming in so-called habitable orbits.

But experts attribute these findings to the limitations of technology. Smaller planets in more comfortable orbits around other stars simply can't be detected. Yet.

How many Jupiters?

All this in mind, Lineweaver and Grether worked out some new calculations for the prevalence of planets that are about Jupiter's size at about the same distance from their host stars. The calculations are based on some of the most recent extrasolar planet discoveries, in which ever-smaller objects are being detected at ever-greater distances from their host stars.

So how many Jupiters are out there orbiting Sun-like stars in the Milky Way Galaxy?

"At least a billion, but probably more like 30 billion," Lineweaver told SPACE.com.

And the math behind that?

"There are about 300 billion stars in our galaxy. About 10 percent (or 30 billion) are roughly Sun-like," he explained. "At least 5 percent (1.5 billion) but possibly as many as 90 percent or 100 percent (about 30 billion) of these have Jupiter-like planets."

These estimates would vary based on exactly what you call Jupiter-like or Sun-like, Lineweaver said.

What about Earths?

The calculations, which are part of a paper that has been submitted to the journal Astrobiology, don't bear directly on worlds like our own. But with what's known of planet formation, some speculation is possible.

"A reasonable guess is the same number of Earths as Jupiters," Lineweaver said.

That, however, depends heavily on how one defines Earth-like. If one includes rocky planets in general, like Mercury, Venus and Mars, "then they are probably more common than Jupiters," he said. If, however, you mean rocky planets with liquid water at the surface, "then we really can't answer that very well. They may be as common as Jupiters, or they may be much less common."

Alan Boss, an expert in planetary system formation at the Carnegie Institution of Washington, said the new calculations for Jovian twins seem reasonable. Trying then to estimate the number of Earth-like planets requires "a leap of faith, but one which appears to be plausible," he said.

"As the veil covering the unseen portions of discovery space is lowered in the next decade, I expect we will find that Jupiter-like planets are commonplace," said Boss, who was not involved in the new study. "Whether or not that also means Earth-like planets are common can only be proven by NASA's Kepler mission."

Kepler, recently approved to launch in 2006, will monitor 100,000 stars for telltale dips in light indicating an Earth-sized planet in an Earth-like orbit has crossed in front of the star. While it would not take photographs, Kepler could provide the first census of planets that have the potential to support life.

SOURCE

<< Home